Saturday, June 17, 2006

My Beard's Near Death Experience......

Much to the chagrin of my mother, as well as a few other important people in my life, I have had a beard since I was 17. At this point I have gotten used to looking in the mirror and seeing some form of facial hair staring back at me. While it’s not a particular point of pride or anything, I have just gotten used to it, and have come to recognize it as a part of who I am. Then the other night came along. I went to Best Buy in Alexandria and bought a beard trimmer. I stood in front of the mirror and trimmed down my beard to a level 1 on my new trimmer (the lowest setting on the trimmer) and low and behold, it looked simply like I hadn’t shaved in a few days, and for the first time in nearly 7 years I have a fairly clear view of my chin. Now I know this really short beard thing is in vogue, though my intent was simply to be a little cooler in the noon day sun. (Frankly anyone who knows how I dress and knows of my inability to wear anything fancier than a Red Sox or Patriots Jersey and Jeans on many occasions knows that to be the case.)

The thing is though, I looked in the mirror, and I saw and still see a different person. Sometimes we all can get an image of who we are stuck in our head, and sometimes that image that gets jammed in there is an image of how we are too. Often the things which dictate this for us are superficial realities (like my beard) and when we get rid of them we can be left a little disoriented sometimes. The reality remains however that we are still the same person, and perhaps by letting go of those superficial things we see something we haven’t seen in a long time. Practically, this can mean something as simple as shaving one’s beard, but the reality holds for things which are much more sublime too. We can often stack roles and self images on top of the image and likeness of God which is in each of us, so that it becomes so obscured that it becomes hard to recognize when we pull all of that other stuff away. For me the temptation is in the image I have of myself as philosopher, as a particular type of friend to some people, or in the role I feel like I should play in community life. None of those things are necessarily bad, but they need to all be subservient to the reality which lies underneath, the reality of the Holy Spirit within impelling us, pressing us forward, and bringing us together in the most important of ways, as Church, as the Body of Christ.

It’s strange, because when we let those images get in the way of seeing the image and likeness of God in which Genesis tells us we were all created we engage in a perverse sort of idolatry, an idolatry of the self. In this idolatry we become worshipers of our own selves, our own egos. We can become strangely self obsessed, and even the vocation that God has called us to can take the life out of us. But if we are really worshiping God, and if what we really seek to venerate is the image of God within, then that vocation, and any other role becomes what it was meant to be, the relationship of love made manifest through actions. Then that role, that self image can, in the proper context, be what St. Ignatius talks about in the Contemplation to Attain divine love, it can be a sharing in love which manifests itself in deeds more than words.

So my beard suffered a near death experience…. It’s till there to some extent, I think I will let it grow back. Some members of the community here in fact have already told me that they miss it. It’s not a bad thing, but like all things it’s good to remember that the most important self image I can have is the image and likeness of God.

Monday, June 05, 2006

On Call and not sleeping......

So I am the chaplain on call here at Georgetown university hospital and I can’t sleep. The call room we have is a claustrophobic’s worst nightmare and it seems every time I am getting to sleep my pager goes off, and here is the catch… its dealing with stuff I feel woefully inadequate to deal with. I am good working with the poor, and with young people, but I am really ill equipped in many ways to handle death and dying. Some of it is my meticulous nature, some of it is a real and deep desire not to look foolish, but most of it is really wanting to help and feeling my complete and utter poverty of spirit to do so.

Poverty of spirit, it manifests itself in me both as a real need to rely on Christ and as my own inability to do this kind of work outside of his grace and his love for me. Metz was right to say that poverty of spirit is the foundation for the rest of the beatitudes. Sometimes too I think it might be precisely being in that moment of having no idea what to do that we actually end up doing the right thing, perhaps even in spite of ourselves. The gospel says that Jesus wept at the tomb of his friend Lazarus, even though he would raise him from the dead a few minutes later, something about that experience left even Christ himself in his full humanity stand before death and feel what every human feels in front of it, confusion, frustration, anger, and sadness. The letter to the Hebrews says that we have a high priest who bears all of our iniquities, and so I suppose he bears this too. All of that also leads to the moment of realizing just how dependant upon the Father each of us is, a moment in which the sharing of life between Christ and the Father made Lazarus come out of the tomb. Without this moment of poverty of spirit we can never really live in that connection.

So its 2:40am and I will with the psalmist await the dawn, knowing that in the dark sometimes we are left only with our poverty of spirit.

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Why Philosophize?

So this past week as I have been finishing up my papers and such I have been asking myself the question of just why it is that I study philosophy like I do. I have already more than fulfilled the Church’s requirements for one preparing for ordination, and I am doing a level of MA here at

the university which no Jesuit has undertaken in

22 years. Why do this? Frankly, its more frustration than its worth in those terms. Ellacuría, who I am writing my thesis on, had it right when he wrote:

“Philosophy as the search for the fullness of truth- not the mere absence of error, but the full presence of reality- is thus an indispensable element in the integral liberation of our peoples. When those peoples count on the real possibility of thinking for themselves in all the orders of thought, they will take the path of liberty and of full possession of themselves. That is what philosophy is for.”

Sometimes I find that my activists friends think of philosophy as just a goofy mind game, and that the only way to free people is just to be down in the trenches, that this is a waste of time. I think they’re wrong, (though I still love them) and maybe a bit impatient. The whole ideological superstructure of the world has to change for people to be genuinely free, so I write.

Sometimes I find my philosopher (and theologian) friends don’t quite get why it is that I do go out into the trenches, to places like El Salvador. They sometimes view it (I think) as a waste of good studying time. I think they’re wrong, (though I still love them) why would we do philosophy if it means nothing to real people? It can become just as banal and oppressive as anything else if we don’t have genuine contact with the real world. Plus the world is a beautiful place, why do philosophy if its not worth saving?

To serve Christ poor and voiceless in the suffering and oppressed, that’s why I do philosophy. I can’t do meaningless overly abstract metaphysics, I just need to stick here and do stuff that genuinely makes a difference in the lives of real people. This is why I do philosophy, and this is what philosophy is all about at its highest moments. We pray in the Our Father: “Thy Kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” That the kingdom of God may become even more of a reality on earth and ever more closely resemble the kingdom in heaven, that is why I do philosophy.

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Emmaus and the Stranger

The Gospel story of the road to Emmaus strikes me in a way it hasn’t yet to this point. The story of the road to Emmaus is not only the historical account of two men encountering the risen Christ, but it is in so many ways a parable unto itself.

Traveling the roads alone in Jesus’s day was dangerous, one was likely to be robbed, beaten, even killed. Being out on the roads alone at night was even worse. The two disciples encounter a stranger on the way. This was a man who was along the way and had no friends, no place to stay, and so they lived out their faith by bringing him along, by sharing with him what little they had in their companionship and material goods. Even in the midst of their confusion, their doubt, their insecurity they lived their lives committed to who they were, out of the dispositions of love and hospitality which had grown in their hearts by encountering Christ. On the road they met the stranger, who took them in to himself in so many ways.

On the road the road to Emmaus the stranger taken in taught the disciples who they were, who Christ was, who God was. Their hearts burned because in their midst was the Son of God, but so often it is in welcoming in the stranger, the outcast, the oppressed, that we discover who we are in God’s light. It is in welcoming in the stranger that we are challenged, shaken from the complacency of our confusion and ambivalence and radically made to choose… to remember who Christ is for us.

They knew him in the breaking of the bread.. They knew him in sharing what they had with him. They knew him in welcoming him, a stranger along the road, in to their home, into their lives. Without regard for their personal security, without worrying about how much food they had, they welcomed him in. That is how they knew him. The recognition of the risen Christ comes in hospitality, in welcoming in the stranger. The story is evident, the parable is simple. We come to know Christ in welcoming the stranger, the outcast. We come to know Christ in breaking bread with those who have none. We come to know who we are by listening to them, by hearing them with new ears. Our hearts then burn with the love of the one who loved us to endure Good Friday, and come to us even as the stranger on Easter Sunday

Friday, April 14, 2006

Obedience, the Cross, and Liberation

Paul says that Jesus was obedient suffering on the cross even unto death. Obviously I have been thinking about this a lot all of lent. As Religious, obedience sometimes encourages us to take up crosses we would never choose for ourselves. There is a value simply in that act alone. Jesus never said “pick up your dandelion and follow me” or “pick up your remote control” or “your Playstation 2” it was something hard, something brutal, it was to pick up the cross. I realize now that obedience to the will of God, for religious but also for everyone else committed to living Christian life, particularly when it is obedience to do something which, like Christ, we want to cry out to the father saying “remove this cup from me!” is not only obedience for the sake of doing God’s will, but it is the imitation of Christ in its very heart, sacrificial, and a real surrender (not simply resignation) to the love of God.

This life is hard some times, let no one convince you otherwise. It is immeasurably worth it though, and not in the sense that the world thinks of worth either. Living a life of Christian discipleship is living the life which makes us most fully alive, and that is what it is doing for me.

The people of El Salvador have been in my mind and on my heart lately too. Maybe it is because I am working on a paper using Salvadoran philosophers. But it strikes me that they have helped to teach me this lesson in their joy and generosity in the midst of the suffering they still wrongly endure. The mystery of the Cross teaches us that obedience to the will of God is about imitating Christ, even to the end. That imitation of Christ necessarily has to include being with the people Christ first came to, the poor. Proclaiming good news to them, as Christ did, proclaiming their dignity, their value, their liberation. Taking up the cross means standing with those members of the Church, which just is the body of Christ, who are crucified, and asking along with Ignatius meditating on the crucifixion.. what have I done for Christ, what am I doing for Christ, what will I do for Christ?

Monday, April 03, 2006

What the Rooms of St. Ignatius are Teaching Me.

Brother Pozzo's Fresco at the entrace to the rooms to Ignatius to the left.

Have you ever had the moment, joyfully, when you have felt like its time to get back to something more basic, more rudimentary about who you are to remember where God’s grace has been?

I think that’s me right now.

Now don’t get me wrong, my life is great, and I am grateful for the way things are going, but at the same time I think it may be good to get back from time to time to that space that you can remember God calling you from (spiritually and mentally) to reap greater benefit from it.

Now obviously I am not talking about going back to Westerly, Holy Cross, or the Novitiate. (all three places which I have a very deep love for granted.)What I am talking about it perhaps more like this story.

The rooms of St. Ignatius in Rome are obviously considered by many to be a very holy place. This was the space in which he wrote the constitutions, sent Xavier to the East, and governed the Society in its early years. Over time, in order to honor the holiness of the place pilgrims came and left behind gifts, the Society started decorating more and more until some 20 years ago, after nearly 450 years, the rooms would have been unrecognizable to Ignatius. They were baroque in every sense of the word, golden altars, candles everywhere, even a goofy looking mannequin of Ignatius. (In other words every little bit of bad religious quiche that one could imagine)

The society decided to strip down everything that had been built up over the years to get back to the original spirit of those rooms, to their original aggiornamento. Now the rooms are back to something much simpler, much more recognizable to Ignatius himself probably, and people seem to love them more than before. Stripped down from all of the baroque and back to their original simplicity, where people can commune with the spirit of Christ present because of the holy man who lived there.

So it is with me, and I think with all of us as we walk down the path of life in Christ. Occasionally we need to admit that we have gotten too baroque, to flowery, stuffy, and maybe even a little full of ourselves. Its then we have to go back to that moment when we really first heard the call of Christ to “come follow me” and began to do it. Obviously, as Catholics we have confession, and I have been faithful to that, but moreso sometimes its good to go back and remember what it is that got us here in the first place, to let ourselves become more and more like that Child in order to enter the kingdom more readily. Remembering those first moment of our walk with Christ I think fill us with gratitude, can overwhelm us with joy, and reinforce us wherever we are in our spiritual life. Obviously not to deny how far I have come and how I have grown (no one wants the current general to move back into those few rooms and govern 20,000 men and the world’s largest single religious order from there) but simply to be able to remember, reclaim, and marvel at how God’s grace continues to move in our lives, that’s not such a bad thing. So in these last days of lent, I am stripping away all of my baroque outwards show and pomp and getting back to the bare walls underneath, that bear a far greater story than the decorations which cover them.

Saturday, March 25, 2006

The Guys I Live With..... Part one in a possible 23 part series

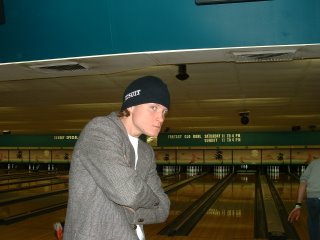

Meet Ben Bocher, S.J. ..... Man.... Myth..... Legend... Engineer in Training..... World Class Marathoner (No Joke)..... Jesuit Scholastic. Ben hails from the mighty north, the Wisconsin Province. Right now he is studying engineering over at the Wash U here in St. Louis. Last year he nearly would have won the St. Louis marathon (the paper in town had him as one of the favorites) had it not been for drinking some bad milk the night before. His specialty in engineering is building water treatment for the third world, starting chapters of engineers without borders, and some other stuff that I have no hope of ever understanding.

When we were all in Central America this past summer, a new word was coined (in Spanish) to describe just how Ben behaves, "Minchar" which means to eat like a vaccum cleaner; (hence the bad milk the night before the marathon) to run 14 miles a day no matter the elevation, heat, or possibility of bodily harm by nature, man, or beast; to know everyone in a 14 block radius; and other assorted things.

This is a picture of Ben looking particulalry thuggish, notice the Jesuit stocking cap nonetheless. His other past times, other than looking slighty thuggish, include karaoke (which is not a good idea) bowling, and general tom foolery. A more generous, good hearted, and kind man you are very unlikely to meet however, and on top of it a man commited to living in God's grace. Underneath the fun exterior is a man of deep prayer, solid faith, and a willingness to lead others joyfully to the love of God he has experienced. He leads a discernment group over at the Catholic Student center at Wash U, and also has been active with retreats there as well. Seriously good guy who I am blessed to call my friend.

Friday, March 24, 2006

Some Nascient Philosophical Musing........

I wrote this little bit of philosophy a little over 5 years ago now. It was my first attempt at writing legitimate philosophy, and it tried to prove the existence of God. (yep, I know, way to start small) I know now that it is certainly not Thomistic, or even necessarily orthodox (philosophically speaking). The way I try to construe God is also possibly problematic. This was, however, enough to win the Markham Memorial Prize in Philosophy at Holy Cross, so while it needs to be worked on a bit, it still may have something to it. Anybody with any thoughts on this let me know. It is archived in the Holy Cross Library in Worcester, MA, (in other words, I have proof that it is my original work) so enjoy it, comment on it, but please don't rip it off, especially because it is still problematic in my mind. Ok that's all.

Mike

Fides Super Rationam

By Michael J. Rogers, Jr.

A.M.D.G.

With the heights and depths of humanity, we seek to understand the world around us, we have created physics, biology, psychology, chemistry, sociology and every other science to explain why that which is, is. We seek understanding through knowledge, we seek to understand more and more why things are here, why they exist, both good and bad, and what we can do to have some control, to be masters of our own destiny. As we break things down into infinitely smaller parts, as we analyze the stars and the universe, as we build the ability to destroy ourselves, to truly choose life or death for the planet, we come to one undeniable truth, everything changes. It seems as if nothing stays the same, seasons change, organisms are born, grow, live, and die, the inanimate is moved and shifted and molded into something new, or made seemingly animate as we breathe the life of our own knowledge into them. All things change, all things posses the ability to be something that they are not, and all things that are once were something else. We can see that when Aristotle made the case for actuality and potentiality that despite all of our scientific advances, this is perhaps one of the few clear truths about the world, that what exists in actuality has a potential to be another actuality. Within time and space, change does not end because time does not end. We know that logically actuality and potentiality must be, in some way, separable, or else we would not be able to define them at all, or even conceive of them as concepts. Within the world we are able to make sense of things because we can boil them down to their parts, and in doing so understand more clearly what it is that causes something to tick, to exist, to be.

The same must be true with potentiality and actuality as concepts, there must be some way to divide these and understand them more clearly as a result. Within time though, we know this is not possible, nothing can be fully actual, because it has some potential, if only to be moved from one space to another. At the same time, nothing can be fully potential, because in order for it to exist at all it must first be something. The two seem inseparable, except if we remove time. If we remove time then we come to understand the nature of what it is to be unchangeable and unchanging, to be both fully actual and fully potential, and in this place outside of time we know that full potentiality and actuality must exist. This is apparent because if full potentiality and actuality did not exist outside of time then there would be no change in time because the two most basic principles of change, that something has the ability to change and that change has some effect, would not exist. Simply, we know they are inseparable within time, yet we know that in order to exist they must first exist as principles independent of each other. Just as we isolate things in nature in order to show their function and definition so must we be able to isolate potentiality and actuality in order to see that as principles of change they must exist separately, if only outside of time.

We can see, however, that as principles of time actuality and potentiality are limited to a subject, something that possesses both full potentiality and actuality separate and distinct from one another, furthermore this subject must exist outside of time. In saying that this subject possesses full potentiality, we say that it must posses within it all of the possibilities for the universe, that it must in essence be all powerful, and through its potential nature creative. Through its actual nature that which exists outside of time must also be all actual as Aristotle said, and as such must be the driving force behind the universe. Furthermore it is impossible for more than one thing to exist fully independent of time, as there is no true concept of space, for without time we cannot place one thing at a point of reference in the plain of existence. For example, what makes something essentially occupy a space is that it occupies it at a certain point in time. St. Peters is in Rome because it is there now, but were we to move St. Peter’s, it would no longer be in Rome, and yet now it is still in Rome, any movement would be in the future, and therefore the dependence of its place in reality is largely dependant upon its place in time. If something exists independent of time we know then that it must not only be immutable, but that since any interaction with anything else would cause some change, that things totally independent of time must be singular. In essence, there must be a God, a creator and final cause that exists independent of time and singularly so.

In looking at this argument several questions arise: First, what is the fundamental nature of change? Second, is it necessary for things to have an actual and a potential nature? Third, must we separate in order to define what actuality and potentiality are? Fourth, in what context can we separate actuality and potentiality, and why? Fifth, can we conceive of that which is outside of time coming from our temporal understanding? Finally, Is it necessary that there be a God existing outside of time in the context of potentiality and actuality.

First we ask what is the fundamental nature of change. It would seem as previously stated that all things change, the earth and the universe itself seem to be in constant flux, as the universe expands and the earth is governed by the laws of nature which in turn bring season to bear and life to flourish and to die. Paradoxically it seems that change is the only constant we can conceive of within time. The only thing that seems inexorably constant is that in fact nothing is constant. Even our own existence is not a constant, but rather the reality that we are conceived, born, that we mature, age and will die is in fact constant. Inherent within change is that we change from one thing to another, from one actuality to another. What we are actually now is vastly different from what we actually were as infants, the only thing that remains is the fact of our humanity, but even in that context we are a different actualization of what it is to be human. Clearly one that attends university and sits down to write within some confines of reason is different from the child who knows little more then to cry for milk when it is hungry or sleep when it is tired. Therein we see two different actualities, within nature as well clearly a seed that falls from a flower is different then the flower that is will become, there are two different actualities of one being. Change itself is also laden with potentiality, for which all things in the universe in their mutability must possess. For a thing to change it must first have some actualization, it must be something, but it must also posses the ability to become something else, it must possess some potential. There must be some driving principles within it that cause it to move, to change to morph into something new. Clearly one cannot become a learned scholar if he does not possess first some intellectual capacity, some potential to become something else. Likewise, the seed that falls from the flower does not become a flower itself unless it first possesses within it the necessary parts of a flower, the small seedling that emerges with time. Even that which is inanimate has potential this can be seen more clearly through the example of a rock, which when chiseled and put in order becomes a beautiful sculpture, this is not possible unless within the very nature of the rock there already exist the potential for it to be sculpted. Therefore the principle of change is predicated upon two primary principles that must exist if in fact change exists. Change must exist however, because we experience that which we know to be change all around us.

Next we must examine the necessity of things having a potential or an actual nature. It would seem that it is not necessary for things have both an actual and potential nature, yet we do know the changing nature of the universe, that which exists changes. Therefore it would seem inherent with existence comes change, and that which changes must have a potentiality and an actuality, therefore having both a potential and an actual nature is necessary to existence. No thing can exist without change within time, we witness this everyday, from a fleck of dust flying off of our shoulder that had previously been there, to the birth of new life, there is constant change, both within nature and in man made interaction, things will always change. Therefore it seems necessary for all things to have a potential and actual nature.

How do we come to an understanding of potentiality and actuality, must we separate them to understand them? It would seem that we could only understand actuality and potentiality in the context of each other. Thus far we have only spoken of these concepts in those terms, however, these seem to be imperfect actuality and potentiality if only because they seem to operate not as ends in and of themselves, but as means to yet another actuality and potentiality arising. The seed falls into the ground and grows to be a flower only to produce more seeds, which will fall into the ground and produce more flowers. The potentiality of that seed to become an actual flower then shifts to the potential of that flower to produce more seeds. The human works hard to make money, in making that money he hopes to achieve some semblance of happiness and security. The human works hard to attain the actuality of having money, which carries with it the potentiality for some sense of happiness. Each time a potentiality produces an actuality that actuality has a potential to be something else. The kind of potentiality/actuality exhibited is imperfect. There is, however, movement that is observable, from highest potentiality to highest actuality, all things move from what they were to what they are becoming through each change what something is to become becomes more apparent, we can say that there are degrees of potentiality and actuality. A child has more potential then a ninety-year-old man, just as a seed has more potential then a withering flower. The child is free to become whatever it will and be whatever it will in the context of its society. The seed may become a flower with many different colors and can produce many seeds. Conversely the ninety-year-old man has more actuality then a child and a withering flower more then a seed. The ninety-year-old man has lived more life and simply understands better then the child what it is to be human to have life. The withering flower has been a flower it has reached some actualization. From this we can see degrees of actuality and potentiality within all existence. If there are degrees of actuality and potentiality then there must be pure potentiality and pure actuality by which all other actualities and potentialities are measured, therefore it is apparent that there must be pure potentiality and actuality.

Since we now see that there must be pure potentiality and actuality, we must see under what context they exist. Change demands time, what makes something essentially different is the two fixed points within time that it is referenced, from that we can observe change. It is also this very concept of time, which makes change possible. If, however, we can remove time from existence, it would seem that change would be impossible, therefore the unity between actuality and potentiality is no longer feasible, as such, we see that potentiality and actuality must exist outside of time as pure and independent of each other. Can we say that there is a place independent of time? It would seem not in that all of history is marked by time, and our human understanding of existence is inexorably bound by time. Before the universe came into existence, however, time would not have existed for two reasons: The first obvious one is that before the creation of the universe there were no stars, no planets, and from that it becomes obvious that there can be no time because there is no daylight by which one could measure day and night. The second, albeit slightly less obvious reason, is that without humanity to observe the form of time in nature, there is no time. If we ourselves had not first conceived of time it would not exist, however, as soon as we began marking the days and nights, plotting the lunar calendar to mark the months, and tracking the changing seasons to determine a year, it began to exist. Without this it is possible to say that time would not exist in some strange way. While change would still occur in this context, the idea of time would not exist. If we can place ourselves in that place before time and the universe existed though, it becomes more apparent that time can be transcended, just as ideas and beliefs can transcend time, as basic mathematics and belief in religion broadly have, and while our ways of looking at these things can change, the ideas and beliefs themselves do not. Furthermore though, in that place before time there exists full potentiality in that all that can be done must first exist here, any possibility exists within the space before creation. Also in this space must exist full actuality, because this space is neither made no better nor any worse by creation, which has to exist independent of it. We can also say of this space though that to some degree all things that exist within it must essentially be one, because without time we have no way to differentiate what takes up different spaces, and therefore any conception of separateness is clearly impossible.

Any speech of that which is outside of time would however seem to beg the question of our ability to conceive of that which we have never actually encountered. It would seem that any talk of that which we have not actually encountered is frivolous if not fanciful, as if we were speaking of unicorns and leprechauns, for these are things which no person has ever encountered and yet we say that we can conceive of mystical horses with golden horns attached to their heads and little men with magical powers, while knowing that they do not exist. The difference seems to be that we know that the universe at some point began to exist, without even presupposing the existence of God, as many who would deny the existence of God would still ascribe to theories of a big bang and evolution to explain the birth and development of the universe. If we know that the universe began, then before that beginning was a shapeless timeless void, and that which can exist independent of all creation. Time comes to be when nature is formed, when planets begin to spin around stars, and the entire universe begins to rotate. Therefore there must be a place outside of time, for even as astronomers tell us our universe is ever expanding, there must be a place for it to expand into, and that is a place untouched by creation that exists independently of it, a place where time cannot and does not exist.

Finally the question arises of whether we can say that that which exist outside of time must be God, it becomes at this point a matter of word play. We know that that which exists outside of time is fully potential, and therefore to some extent acts upon creating all that is and all that ever has been. We also know as Aristotle said that that which exists outside of time is fully actual, and therefore is the greatest actualization of all things, it is that which all things by their nature try to emulate in their own way, as Augustine says “all nature cries out that it is created.” In this capacity as full potentiality too it must be omnipotent, as all possibility for the universe lies within it. As full actuality also that which exists outside of time must be omniscient, it must know all things because it is the fullness of all things. Furthermore because it is outside of time we can say that it is omnipresent, since it is not ruled by time or space. Also, because of its timeless nature that which exists outside of time must be immutable. It would seem then that that which exists outside time must be all of the things which one would ascribe to God, and whether we ascribe to it the name of “God” or any other arbitrary name the reality of the nature of that being which exists outside of time remains the same, as all powerful, all knowing, ever present, unchanging, as God.

What philosophical discourse can say of the existence of God however pales in the light of what faith can know of God, reason can only take us this far, to know that God exists. Faith is what drives us to further understand this conviction and come to know the God that drives the universe from creation to finality, that causes the moon and stars to turn, the night and the day to happen, and is present at every moment of existence in every moment of existence. The God that moves over the waters of the seas, in the rushing of the wind, and in the all consuming heat of the fire cannot be understood by reason, and all that human mouths utter as Thomas Aquinas once offered “is mere straw” in comparison to the actual reality of God. To those with faith, any argument from reason for God’s existence serves only to examine faith from a different perspective. For those from outside of faith the intellect may serve to except the possibility, but those who ultimately reject any argument for God’s existence have closed themselves off to it already, for God can only be seen through the eyes of faith and poorly understood through reason.

Does God Exist? It would seem that He does, and He dwells within the hearts and souls of each man that struggles to show by reason that which by is made evident only by faith. To rise to the heights of Godly contemplation one must seek not the reason which one can argue from, one must seek the simple faith of a child, knowing that what we seek in reason can be found only through the eyes of faith. All to easily one may dismiss through reason what others know in faith, but those who hold in faith that they are children of a living God will never be put to shame, for the light of reason can bolster that which they have known, that in this world, all that potentially may be, and all that is to come flows from an eternal creator, and that all that we are longs ever more for the light of that presence which guides us ever closer to the fullness of who we are. To be fully human, to walk in the light of that which we are, not simply what we should be is to be in the presence of our eternal creator, and to stand in that presence is something which reason cannot explain, although it tries. One may all to easily dismiss this argument or any other, to say that God does not exist is too easy, for then our freedom becomes license and our lives inconsequential, and somewhere we all seek to deny God so that we may be free to walk by our own reason, just as the enlightenment fathers sought. That freedom has fallen short though, for if by freedom we allow others to starve, if by freedom we can legally kill others because they cannot speak for themselves, if by that freedom we are free to be enslaved by greed or desire for power, then we are not free, then we are not human. To know that God exists is to know that there is an end to which all things move. To know that God exists is to know that there is a place from which all things came. To know that God exists is to know that we are made higher, our reason for something better then ourselves. Our reason can let us know that God exists, even in that which we cannot fathom, eternity. Our faith is what ultimately brings us ever more into the light of all that we can be, all that we are, and all we will be, in that light we can only hope to stand in awe and silence before that from whence we came and to where we are going, God.

Some past Reflections

Mike

The Feast of the Presentation of the Lord

Wednesday, February 2, 2005

Given at the House Chapel of the Bellarmine House Jesuit Community

St. Louis, MO

Today bears special meaning for those of us who are religious. It is, for those here a day of special meaning, it is the anniversary of Carlos’s vows, and it is the day when two years ago Waldo and I completed the Spiritual Exercises. In the universal church, it is the world day for religious, and the celebration of the Feast of the presentation of the Lord in the Temple. Today we should hear the message anew of the great blessing of our vocation as men consecrated to God by our vows, we should recognize the faithfulness of God in our lives, and we should be renewed in our watching for that in breaking of the Lord coming to dwell in the world and be always prepared to set a path before him. Today we hear the story of Simeon and Anna, we hear the Psalmist crying out about God entering his own house, we hear of God’s promise to send his messengers before him from the prophet Malachi, and we hear the good news of Jesus’ dwelling among us from Hebrews. Today we hear of that driving force behind our lives as religious, to wait on the call of the Lord, and prepare the way for him in the world. Even as Anna and Simeon did 2000 years ago.

How wonderful it is to be the messenger to go before the Lord, preparing the way for him. At all moments, by virtue of the relationship we have with God, each believer is called to be that messenger, preparing the way before the Lord not only who is to come, but for the Body of Christ present in the world which is the Church, and for the increasing realization of the indwelling of the Spirit in the world. And while it is a blessing, it is certainly not always easy is it? Malachi says that those who serve the lord in this way will be refined like Gold or Silver, sometimes it would seem that the process of bringing out our purest and fullest selves necessarily involves being cast into fire, and lovingly, patiently, drawn forth from it again. Yet for Malachi, this is a precondition of the Lord’s coming to dwell among us. For Simeon and Anna, the long years of waiting, indeed of thirsting for the presence of the Lord very well could have been the fire in which they dwelt, growing ever closer Yahweh in the crucible of prayer, which refined them and drew them closer to the small child they would encounter in the Temple. So it is also for us, and sometimes I think for those of us who are younger in religious life it is important to remember that our prayer serves a purpose, our lives of work and the self denial and discipline which often must come along with study, should help serve to draw out the fullness of who we were created to be in God’s eyes. There are no doubt times in which it is a struggle, times in which places which are being refined in are painful, or perhaps there are even places we hide from the fire which seeks to make us whole. But as the author of Hebrews tells us, this coming of Jesus among us means that for those of us being tried and tested we have a God who can help us, because he himself was tested through what he suffered. For us as Jesuits, we wait for apostolic life often enough in the same way Anna and Simeon waited those long years in the shade of the Temple of Jerusalem for Christ. It seems fitting that we do this, for we seek to find Christ in all things, indeed we seek to find him in the world we can so often in the midst of studies long to be missioned too.

We need here to remember too the simple fact that God always keeps his promises. That God is faithful in the same way he was to Simeon and Anna, and indeed to all Israel. The words of Simeon, “Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace, according to your word, for my eyes have seen your salvation, .which you prepared in the sight of all the peoples: a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and glory for your people Israel.” Echo a simple truth that we can both now profess and one day hope to be able to more fully. That is that God is always faithful to us, even in the midst of our waiting and of our anticipation. This simple truth that we can remember and rejoice in as Anna did as she danced in the presence of the newborn Jesus: God ALWAYS KEEPS HIS PROMISES.

Remembering this faithfulness is also remembering in a very Ignatian way those moments when the in-breaking of God into the world have left us filled with Joy and gratitude. Knowing God’s faithfulness also knows that Jesus continues also to break into the world. Simeon indeed witnessed what the psalmist sang of when the words “Lift up, O gates, your lintels; reach up, you ancient portals, that the king of glory may come in!” trickled forth from his mouth. God dwelling in God’s own house in a more profound sense than he had ever before, no longer was it simply the presence of God in the long lost Ark of the Covenant, but rather God’s Son come to broker the new covenant in his own blood. Yet this moment of Christ coming to dwell in his temple is not lost to the one moment of time so long ago, but rather it is brought into the newness of the present each time we gather around this table, in the Eucharist, in the Word, in the Presider, and in the community gathered here. In that way, for us as religious this table serves as the center of our lives and continually challenges us as we come around it to witness the in breaking of Christ in the world in each other. This realization of God dwelling among us, indeed of God fulfilling his promise to us often both strangely and wonderfully through the community in which we live is a promise which extends beyond this chapel, beyond these doors, and into the world in which we live. Indeed we see Christ dwelling in our brothers and sisters in the world, as God so often fulfills his promises to us through them.

In the midst of the silence, in the midst of what in studies can seem like a constant advent to our lives to come, we must share in this, the final official day of Christmas joy in the Church calendar. It is a joy which recognizes God’s faithfulness, a joy of incarnational faith that looks for Jesus in the world, and a joy which can wait in peace, knowing that now, and at every moment God’s promise to us is fulfilled. Today, and every day, we should seek to remember the faithfulness of God, and in that to be always looking for those moments when he seeks to enter into our lives, even as we prepare the way for one who is so powerfully already among us. Today as religious we give reason for our hope, and our joy, as we cry out with Simeon that our eyes have seen the glory of God’s salvation.

On Discernment of Spirits, the Two Standards, and the Three Classes of People

Given on the Greek Retreat at Saint Louis University Saturday, February 12, 2005

So far we have talked about our relationship with God, the things which help it grow and the things can get in the way. We have also talked about the ways in which God is ever present in our lives and the ways that God reaches out to us through the sacraments. I am going to talk abut how we make decisions in our lives. How we move, in the context of our relationship with God to make the choices which will ultimately help us to become who we were created by God to be. In the Spiritual Exercise of St. Ignatius there is a section called the Electio, in that section, Ignatius lays out some experiences of prayer which are meant to both make one ready to make such decisions in their lives and to help them to use what he would call a certain disposition to make the right choices.

I think we all know that there are very few important decisions we make which have little to no consequence in our lives. When you were graduating from high school you had to choose where to go to college. Now that you are at SLU you have other decisions to make, decisions about how you will live the rest of your life. These aren’t just decisions about what career you will commit yourself to or where you will live. The decision now should be who am I going to be, what kind of person with what kind of commitments? How am I going to live life with a real and genuine love of God? So how do we make those choices?

As in any choice the first thing we do is look at the options. Somewhere there has to be before we can make those specific decisions a choice about where we stand and what we stand for in the world, this is a choice of what values we will have and how we will live them out. Ignatius gives us two sorts of exercises about how it is we can make those decisions about where we stand in the world.

The first is called the Meditation on the two standards. Ignatius was, in his life before his conversion, a soldier. It comes as no surprise then that in order to help us better understand the two different sets of values that are out there in the world in his view that he wants us to think of two different military camps, with two standards, that of Christ and the Evil Spirit, flying above them. He takes us first to the camp of the evil spirit.

Ignatius sets the scene of people in bondage, of Satan sitting on a throne of fire and smoke talking to his demons. Often when I think of this standard when I try to pray about what a military camp with Satan as the commander would look like, my image changes depending on where I am in life. The first time I prayed with this, it looked like Murder from the lord of the rings, and once when I prayed with it when I was living in a suburb of New York City, it looked like Times square. Fostering an understanding what we think this camp looks like is important, but more important is listening to the way in which St. Ignatius says that the Evil spirit talks. Ignatius says that the evil spirit tells his followers to go out into the world and tempt people first with riches, and then if they get riches people will honor them, once people honor them, they will grow to pride and turn away from God. So the progression is riches, honors, and then pride. When I think of this I often imagine people being enslaved, and in chains. Why? Because it seems that when we make this move maybe we are relying for our sense of self worth on what others think, on how much we have, and in that way we become trapped, we aren’t really free because we can become defined by some pretty constraining conventions.

Jesus offers us something different in his camp though. Ignatius says to imagine it as being set simply on the plains outside of Jerusalem, and as we approach Jesus we hear him speak. Ignatius says to consider the discourse which Christ our Lord makes to all His servants and friends whom He sends on this expedition, recommending them to want to help all, by bringing them first to the highest spiritual poverty, and -- if His Divine Majesty would be served and would want to choose them -- no less to actual poverty; the second is to be of contumely and contempt; because from these two things humility follows. So that there are to be three steps; the first, poverty against riches; the second, contumely or contempt against worldly honor; the third, humility against pride. And from these three steps let them induce to all the other virtues.

It seems so counter intuitive, doesn’t it, to be open to being poor, to having people hate you, and to being humble, and all of this to gain every other virtue, all of this to be who God created us to be, but this way offers us a freedom doesn’t it? We aren’t concerned for money, or for popularity, and we are free in humility to even admit we’re not perfect.

So what do we do with this, we have seen two things to choose, one seems to offer us freedom, but wait there’s more. The thing is we also have to know how to use that freedom if we get it, we need to know how to make choices in light of that freedom, and this is where Ignatius offers us the three classes of persons. Imagine, he says, that you get a couple hundred bucks and you do it in a way that’s not entirely Kosher, your conscience is eating at you, and you want to ease that pang of guilt. What do you do?

Well there are three ways we could respond, we could either just get rid of the money and by doing it ease our conscience. So without even thinking or praying about what would be the best thing to do, they just get rid of it.

Then there is the second group of people who want to do something pleasing to God with it as long as its on their own terms. So it’s like saying “OK God I will fix the problem by getting rid of the money, as long as you approve of me giving it to this charity that I really like.” Basically they tell God what they are going to do.

Finally, Ignatius says there are a type of people who want to do something pleasing to God, but to do it on God’s terms. These people wait to find out what would be the thing to do most expedient to God’s greater glory, indifferent to the money they have acquired.

When we choose, if we do so in freedom, we also have to choose based on a criteria, we have to have an underlying reason for choosing what we do and the idea of that third set of people offers us a reason, that we choose to do something for the greater glory of God, trusting that God will show us what to do and how to do it. But how do we know when God speaks to us? Ignatius says that we can discern spirits; we can discern what our hearts are telling us by paying attention to the movements within.

If we find something which brings us life, which makes us more alive, more fully ourselves, freer, and most importantly closer to God, we have found something which is bringing us consolation. We have to be careful though, because what brings us pleasure or temporary happiness is not necessarily consolation, in many ways it could be taking us away from God. Likewise, something could be really hard, something could be a struggle, like a relationship with someone you love for example, and still bring us closer to God, still make us more free, still make us more fully ourselves.

If we find something which makes us feel empty, alone, isolated, and empty, that thing is moving us away from God into a place of desolation. Even things which seem like fun at the time maybe ultimately unfulfilling and may be desolating us, so we cannot simply equate it with what might seem like a lack of happiness at any moment, but rather with a deeper reality of who we are and who we are becoming.

Given at the Saint Louis University Praise and Worship Holy Hour

Domestic Chapel of Notre Dame Hall

November 22, 2004.

I often tried to sit facing the large windows in the dining room in our novitiate dining room. If I sat facing into the dining room my eyes are inevitably drawn up to a Fra Angelico painting depicting the Annunciation. The story behind why I did this is one of a battle of me against myself, though at the time I would have told you it was an epic struggle of good verses evil, light verses darkness, me against my assistant novicemaster. One night in December of my first year of novitiate I sat in the living room at Arrupe House novitiate with the rest of my community and declared that the painting on the wall was not painted by Fra Angelico, but in fact by another painter named Fra Bartolomeo. Jim, my assistant novicemaster, corrected me, telling me that he had seen the original, but I was still insistent that he was wrong. We finally looked it up on the internet, the modern arbiter of all disputes, and sure enough, it was Fra Angelico. I refused to be wrong, I did everything in my power not to admit I was wrong, I made a statement something to the effect of “It might be a Fra Angelico.” being careful to never actually let the words “I was wrong” come out of my mouth.

I didn’t want to be wrong; I couldn’t let myself be wrong because being wrong meant that I didn’t have it all figured out. I don’t have it all figured out though, I don’t have all the answers, and in fact sometimes I wonder if I really have any of them. Yet this season of advent challenges us to break free of the ways we view the world, to looks beyond the answers we know, and to look to God doing something new, something we once thought impossible. The readings we encounter in this season challenge us to humility, and a faith to allow ourselves to sometimes be wrong, and by it to grow deeper in relationship with the Lord. The readings call us to let God be God, and for us to have faith, even when things seem upside down or nonsensical.

God is doing something new here, and somehow our perceptions of the world we know simply don’t mean much in the light of God’s saving presence. All too often we have the idea that we can and should be able to do things on our own. A story from the book of Isaiah tells us differently though. In this story, Ahaz, the king of Judah, realizes his kingdom is threatened. The Syrians and Ephramites are threatening to over take his land, and he feels as if he has nowhere to turn, except to the Assyrians. God sends Isaiah to Ahaz to tell him to simply have faith and courage; all will turn out ok in the end. To further show Ahaz, God tells him to ask for a sign, and he will have it. Ahaz says that he won’t tempt the Lord, and so God offers him this sign, that a virgin will conceive and bear a son and he will be named Immanuel. How does the story turn out? Well Ahaz somehow can’t get beyond what he knows, he is a king, and as king he knows what to do, so he makes a pact with the Assyrians. He doesn’t allow himself to have faith in what he cannot understand, that against even the most powerful army, God’s promise stands firm. Eventually Assyria, the one time ally of Judah, would invade and lay siege to Jerusalem.

God’s ways are not our ways, and often the greatest call is simply that call to a faith which hopes in what it cannot possibly understand. I imagine there must be something intimidating about the sight of angels, every time they appear to humans in scripture they tell them not to be afraid. Gabriel appears to our blessed mother, and after his greeting he tells Mary not to be afraid, that she is blessed by God, but what he tells her next is perhaps more frightening than the angel’s countenance itself. He tells her that she will conceive and bear a son. Mary’s whole world could have come crumbling down. She wasn’t married; she could be stoned for being found pregnant out of wedlock. The gospel tells us that Mary was “deeply troubled” at first. But the revelation of God’s plan by Gabriel seems to calm her, and the angel encourages her that “nothing is impossible with God.” In this place Mary is being called to believe that she could bear a son without having relations with a man, that she would be taken care of in God’s providence and not be cast out from society, or worse yet killed. Mary is being called to a place where she can believe that her barren cousin, Elizabeth, is with child. The difference between Mary and Ahaz is that she was able to believe and say yes to God’s ways forsaking her doubts and fears, and having faith.

In these days of Papers, Studying for Exams, it might seem best to go on autopilot, to fall back on all we have known. The future might seem even a bit hazy, as the regular way of life we have fallen into over the semester begins to disappear. It might seem like a good idea to remind ourselves of all we have been and done; all that we have identified ourselves as up to this point. God is doing something different here though. The message of these days of advent, the message we have today is one of joyful hope. It is a hope that can let go and let the world, and maybe most importantly ourselves be transformed into whatever God holds for us. It is a hope which holds its arms wide open to the gifts and graces that are coming, and in opening up, lets go of some of the past. It is a place where we can say yes, and allow Christ to continue to grow and make his home in and with each of us. The painting in the novitiate dining room was by Fra Angelico, I was wrong, my assistant novice master was right, thank God.

Given At the Bellarmine House Jesuit Community House Chapel

Feast of St. John Berchmans, S.J.

AMDG

When we celebrated the philosophy and letters mass of the holy spirit at Kenrick seminary earlier this semester, I, being a hot shot new scholastic fresh from vows, was somewhat taken aback by the prayer of the faithful that read something like “we pray for those of us discerning our vocation to priesthood.” I had taken vows as a Scholastic a month ago, I thought to myself, discernment over, should the prayer read “for those of us here who are discerning,” shouldn’t I be somehow left out of this? That is for you just one glimpse into the way in which this mind works. Neurotic? Yes. Prideful? Often. My discernment was done, I had spent the better part of three years doing it formally, both as a candidate and a novice, surely I had taken vows, I had the cross on the wall and the pictures neatly stored on my computer. I certainly remember the ensuing 14 hour minivan ride with Waldo to get out here. Wasn’t this discernment thing supposed to be done?

Of course in one important way, it was. I had discerned to take vows, a step which I knew I was taking perpetually. There is a way in which It never can be though, as discernment of the much more mundane realities of day to day life for each of us ends up being the very thing which both sustains us in the love of Christ and which draws us closer in a creative tension to being able to answer in the immediacy in which Christ calls us, by our very creation to be radically in love, in relationship, and in union with the God who created us and loves us far more than we could ever imagine or hope for.

The spirits of the world which St. John speaks about in our first reading today are very much active in our lives if we are honest. From the seemingly all encompassing reach of popular culture to the deepest most interior doubts and fears, there are things which can serve to draw us off of the path to the fulfillment of who we were created to be. St. John says not to trust every spirit, but to test them. The true test being that the spirits from God must acknowledge Jesus as Lord. How many desires and attachments in our lives still elevate other things in a realm of more import than God? How often still would we rather hold onto old ideas and ideologies rather than being radically open to the word of God? How often would we rather place the value of our work, something which can often be an idol for us as Jesuits, above the importance of our lives of prayer and in front of our commitment to being radically available to God’s will by our vows of obedience, and what about those lingering doubts and fears, those things which are a part of any human life lived in love, which still keep us from the most ultimate reality which is God, who is love. Yet while challenging us to be open and able to read the spirits and signs of the times, John reassures us that we belong to God, and that we, by our love of God which spills over into love for each other, have conquered those spirits which as soon as we recognize them through discernment lose their power “for the one who is in you is greater than the one who is in the world.”

There is immediacy to the Gospel’s call as well, Jesus is heading for Jerusalem, and as the crowds follow him and his disciples he challenges them. He challenges them to leave behind the things which get in their way of following him, of being with him and to follow him, even into uncertainty, without looking back. Jesus’ words are challenging, calling us to let the dead bury their dead, and to follow him as one who sets to a plow and never looks back. How do we do this? How can we live the in the immediacy of the Gospel call while at the same time being open to discerning the ways in which God is present and the ways in which we are present to something other than God in our lives?

It seems an answer and model lies in the life of the saint we celebrate today. The iconography of St. John Berchmans often shows him with a copy of the Constitutions in one hand and a Rosary in the other. He was a man known for his piety and his faithfulness, even and perhaps most especially in the mundane things of life.

A reflection for my grandmother, Mary Rogers.

November 11, 2004

Given at St. Joseph's Church, Newport, R.I.

When I was a kid, visits to grandma and grandpa’s house usually meant one thing to me. It meant that for a few hours I would descend into that wonderful basement on Ayrault St. which was one part bb gun range, one part dart room, and two parts workshop with my grandfather, my brother, whatever cousins happened to be there, and often enough my father and uncles as well. In the mean time grandma would be upstairs entertaining our mothers in the living room filled with the pictures of our fathers as children, those pictures which seemed to be often enough more fantasy than reality. This was the way it was with grandma, always and often welcoming people into her home with a quiet dignity that was sometimes misunderstood, but which always befitted her. It was a dignity that bespoke the way she grew up, in the same neighborhood where Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Mark Twain wrote books like Huck Finn and a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s court. I am sure that in some ways the later was a book whose main character I spoke to the reality of the place from which she came. When I was in High School, I would often pass by that house on Asylum Avenue in Hartford on my way to school, marveling that my grandmother had grown up in this once resplendent neighborhood. I suppose it may have been from this place, from this cultural up bringing, that she learned the manners which would quite properly invite all of the women into the formal living room of her house, even as we savage men took over the basement.

There was a depth to my grandmother far beyond that though, a side of her most of us got fleeting glimpses of, though I suspect grandpa always knew and that was precisely why he is so much in love with her. She was a woman of faith, and a woman of deep care and concern. Somewhere underneath all of that was a woman who was very deeply grateful for the life she had been blessed to live. From December until June I was assigned to teach at Fairfield prep in Connecticut. My work allowed me the ability to visit with grandma on weekends. I would often bring communion, we’d pray together, and talk about how she was doing and what she was feeling. The last time I saw her was during one of these visits. My father and Grandpa had gone into town to take care of some matters at the bank, and it was just grandma and I. She told me about how she had met my grandfather at a beach party in Newport, and how she could have never known that that trip to Newport that weekend would lead to her spending her whole life there. She shared with me stories, none of them edifying enough to share here, of the rare but still real juvenile delinquency of my father and uncles, laughing now at the lessons they learned then. In the midst of all of this it became apparent to me how much she really loved her family, and how much she loved being a mother and a wife. She had found something which had brought her profound happiness, so much so that she was willing to give up her position in an actuarial department to be a loving wife and mother. She had found the pearl of great price and had sold everything to possess it. In this day and age that seems a great gift more and more, to find oneself in one’s calling, not only to a profession, but in the living out of the Christian mystery that is so often found in dying to oneself in the service of those whom one loves. This was an ideal so richly displayed in my grandparent’s marriage and something which my grandfather witnessed to so well for the past 11 months as he has spent his very self to the point of utter exhaustion in service to the woman he has loved so much for so long.

They had both found a way to live in that self sacrificial love which is the very center of our lives as Christians, and they also found a way to live in real gratitude to God for it. Their four sons were all brought up in the Catholic faith, an identity which was so important to them both. The stories I have heard of my father and uncles waking up early when they were young to serve morning mass in this very Church before going off to school evidence this. Their sending them to Catholic grade schools and High Schools, as well as one to a particularly fine Jesuit School in Worcester, and one to a pretty good Dominican School in Providence evidence the kinds of values that they loved so much as to want to pass them onto their children.

While it was a faith that started at home, it certainly didn’t stop there, her service as a Eucharistic minister to the sick and dying speaks volumes to the depth of her commitment to that faith. As one who has worked as a hospital chaplain, I can attest to this being particularly draining work, as bringing the Eucharist to a person who is ill is so much more than just giving them a consecrated host, it is bringing them the presence of the people of God, of the Church, and being present to them when they are often most vulnerable and in need of help. This task, to which she was most faithful, speaks of her commitment to a faith which was very much alive and active in her life. This faith is a rich part of Grandma’s legacy, and it is a faith which must now, as we mourn her loss, be at the center of our life together as a family and as her friends. We must be able to forgive all of the hurts, the pains that come with being human and being in relationship with and to one another and to allow ourselves also to be forgiven by asking for that forgiveness where it is needed. This reconciliation and unity now seems the most fitting tribute to a woman to whom it meant so much. In this way we can evidence the truth that she seemed to so clearly understand, that truth is that in the self sacrificial love that the Christian life demands that we often enough find the cross, but that that cross is redeemed and its purpose made clear in the resurrection. With every deep and dark night, there must ultimately be a new fire, an Easter morning. As we mourn, as we should, we must also have hope that ultimately just as she experiences new life in Christ, so also may we, as those who loved her, experience a newness of life in our unity and support of one another now and for many years to come.

It should come as little surprise that for a woman who was so active, convalescence was a difficult thing. It meant that many of the things she so often enjoyed were simply slipping out of the grasp of possibility. The past 11 months were hard for her, hard for Grandpa, and for her sons, but they were a testament to the love of this family for each other. The words which are so often difficult for us to speak that tell each other of the love and concern we have for one another are still more eloquently spoken through the silence of these acts of love. As is so often the case, people dying find the strength to hold out until their families are gathered around them, and this was what happened with grandma. She waited to see all of her sons, who were very much the fulfillment of her Christian vocation, the fulfillment of what God had created her for. She could then say along with Simeon in the temple, “Lord now you let your servant go in peace, for your word to me has been fulfilled.” Now it is to us to remember in gratitude and continue to make the fulfillment of that promise more and more a reality. Amen.

My First Post

So I am up and Blogging, I suppose I will use this for posting random picutres of cool things, maybe post an occasional reflection that I have prepared for community preaching, maybe some cool philosophy stuff I discover, or come up with. Maybe pictures of the Mike Rogers, S.J. join the Jesuits see the world tour...... I dunno. Honestly we'll see how long it lasts. So here we go..............................

The picture is me on my vow day right before professing perpetual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the Society of Jesus